Summary

Understanding how to calculate and model the hydraulic grade line (HGL) and energy grade line (EGL) is essential for ensuring reliable water distribution systems. This article delves into the fundamentals, from definitions to modeling techniques using tools like EPANET. We will cover step-by-step calculations, including derivations of key equations such as Darcy-Weisbach and Hazen-Williams, and explore their application in pressurized and gravity-fed networks. You will learn to interpret profiles, address common challenges such as negative pressures, and optimize your designs to avoid overflows or cavitation. Practical tools provide actionable guidance, drawing on real world experience to enhance your system efficiency and longevity. Whether dealing with hydraulic grade line calculation or energy grade line drops at pumps, we equip you with the knowledge to tackle complex pipe networks.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Fundamental Definitions and Meaning

- The Bernoulli Equation as the Foundation of HGL and EGL

- Manual Calculation of HGL and EGL

- Computer Modeling of HGL and EGL

- Interpreting HGL and EGL Profiles

- Critical Design Implications

- Common Errors and Catastrophic Consequences

- The “Hidden” Third Line

- Practical Rules of Thumb and Checklist

- Case Study 1: Water Distribution Network Analysis in Chirala Municipality

- Case Study 2: Hydraulic Analysis of a Municipal Water Network with Pumps and Demands

- Conclusion

- Glossary

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Bibliography

1. Introduction

In today's water distribution systems, where demands fluctuate and infrastructure ages, understanding HGL and EGL remains a cornerstone of effective design. These lines enable engineers to analyze pressure and energy distribution, preventing issues such as low-pressure zones that disrupt service or high velocities that cause erosion-corrosion in pipes. As networks grow more interconnected, accurate HGL and EGL analysis ensures resilience against surges and maintains end-use water quality. This article shows how to calculate and model these lines, emphasizing their role in avoiding pressure issues in gravity-fed and pressurized networks.

2. Fundamental Definitions and Meaning

The hydraulic grade line (HGL) is defined as the locus of points along a flow path where each point represents the sum of the pressure head and the elevation head. Mathematically, this is expressed as:

where p is the pressure, γ is the specific weight of the fluid, and z is the elevation head. Physically, the HGL indicates the height to which water would rise in a piezometer tube attached to the pipe at that point, reflecting the available pressure for driving flow [1].

The energy grade line (EGL) is defined as the line that represents the total mechanical energy per unit weight of the fluid along the flow path. It is given by:

where V is the flow velocity and g is the acceleration due to gravity. This builds on the HGL by incorporating the velocity head, and the EGL typically slopes downward in the direction of flow due to energy losses from friction and other irreversibilities [1].

Calculation refers to the process of determining HGL and EGL values at specific points in a system using fundamental equations, such as Bernoulli's, while accounting for head losses. Modeling, on the other hand, entails creating a comprehensive simulation of the network to generate continuous profiles of these lines under different operational scenarios, usually through specialized software.

Engineers perform these calculations to evaluate pressures throughout the system, properly size pipes and pumps, and pinpoint potential weak spots. They engage in modeling to explore hypothetical conditions, refine system performance, and anticipate how changes might impact overall behavior. The significance lies in how these practices influence the dependability of water delivery, operational costs, and the durability of infrastructure. Typically, hydraulic engineers and specialists at water utilities handle these responsibilities. When done incorrectly, outcomes can include pipe ruptures, water contamination, or wasteful energy consumption. For gravity-fed networks, accurate HGL analysis is vital to maintain positive pressures and prevent vacuum formation that could collapse pipes or draw in contaminants; in pressurized networks, EGL assessment is key to positioning pumps correctly and averting cavitation or unwanted overflows.

3. The Bernoulli Equation as the Foundation of HGL and EGL

The Bernoulli equation states that along a streamline in steady, incompressible flow without friction, the sum of pressure head, velocity head, and elevation head is constant:

For real systems with losses, it becomes:

Where hL is head loss. The EGL follows this total, while HGL omits velocity head.

4. Manual Calculation of HGL and EGL

Start with the Bernoulli equation. For head loss hL, use Darcy-Weisbach:

where f is friction factor, L length, D diameter.

Derive Darcy-Weisbach from scratch: Consider laminar flow in a pipe. Shear stress where μ is viscosity. For steady flow, force balance: pressure drop

Velocity profile

Average

Thus,

For turbulent, empirical f yields

Hazen-Williams alternative:

where C is coefficient, R hydraulic radius, S slope.

Derive empirically from experiments correlating flow to roughness [4].

Head loss

in US units (Q in cfs, D in ft).

Example: For a 1000 ft, 1 ft diameter pipe, Q=2 cfs, C=120, h_f ≈ 2.41 ft. (The HGL drops by this amount due to friction, assuming no other losses; EGL drop would include any velocity head changes, but they're minor here.)

HGL vs EGL Comparison for Water Distribution Systems Design

| Aspect | HGL | EGL |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | ||

| Components | Pressure + Elevation | HGL + Velocity Head |

| Graphical Relation | Lies below EGL by the amount of velocity head | Lies above HGL; total energy line |

| Slope | Due to friction and other losses | Due to friction and losses; steeper where velocity is high or changes |

| Behavior in Narrowing Pipes | Dips more due to pressure drop from increased velocity | Remains relatively constant if no losses (energy conserved) |

| Use in Calculation | Pressure checks and determining static pressures at points | Total energy balance, analyzing kinetic energy effects and overall losses |

| Common Application | Simplifies network models by often neglecting velocity head (small in large pipes) | Essential when velocity changes significantly, e.g., at contractions or pumps |

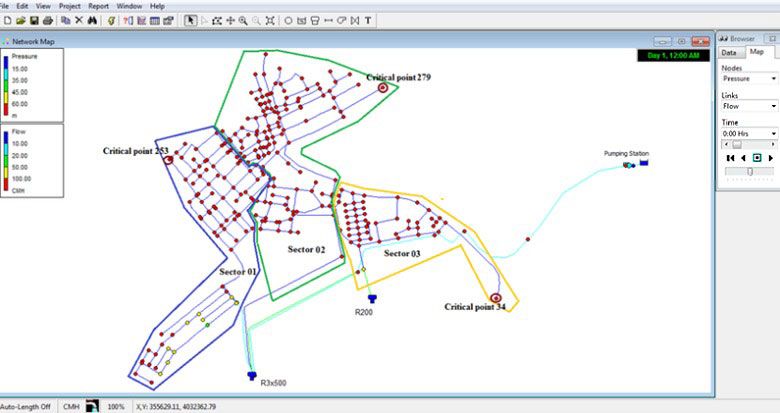

5. Computer Modeling of HGL and EGL

While manual calculations work for simple systems, computer modeling scales to complex networks with hundreds of pipes and varying demands. Software simulates flows, pressures, and energy under steady-state or extended-period conditions, generating HGL and EGL profiles efficiently. We focus on EPANET because it is free, open-source, and widely taught in universities, making it accessible for students and professionals starting out [5]. Developed by the U.S. EPA, EPANET uses the gradient method to solve network hydraulics, balancing continuity and energy equations iteratively. It excels in steady-state analysis but can handle dynamic simulations over time.

Other tools like Bentley WaterGEMS offer advanced transient analysis for surges, while Autodesk InfoWater integrates with GIS for spatial data. EPANET's simplicity suits educational purposes, though professionals might prefer paid options for built-in EGL plotting and optimization.

Project Setup in EPANET

- Download and install EPANET from the EPA website. Launch the program.

- Go to Project > Defaults to set flow units (e.g., GPM), headloss formula (Hazen-Williams recommended for water), and ID increments.

- Under View > Options > Map Options, enable node IDs, symbols, and notation for visibility.

- Set map dimensions via View > Dimensions to define coordinates in feet.

Building the Network

- Use toolbar icons to add junctions (demand points), reservoirs (fixed-head sources), tanks (storage), pipes, and pumps.

- Draw pipes by connecting nodes; enable Auto-Length in defaults to calculate lengths from map scales.

- Add vertices to curve pipes if needed. Label elements with the Text tool for clarity.

Setting Properties

- Junctions: Assign elevations (ft) and base demands (GPM).

- Reservoirs: Set total head (ft).

- Tanks: Define bottom elevation, initial level, maximum level, and diameter.

- Pipes: Input length, diameter (in), roughness (C-factor, e.g., 120 for PVC), and minor loss coefficients.

- Pumps: Define curves (head vs. flow points, e.g., 600 GPM at 150 ft).

- Patterns: Create demand multipliers for time-varying scenarios (e.g., peak hours).

- Controls: Add rules like "pump on if tank level below 50 ft".

Running the Simulation

- Access Project > Analysis Options to set hydraulics (Demand-Driven Analysis), time steps (1 hour), and duration (24 hours for extended periods).

- Click the Run button. EPANET iterates to convergence, computing flows, heads, and losses.

- Check the status report for errors; adjust tolerances if needed.

Viewing and Plotting HGL and EGL

EPANET focuses on HGL via hydraulic heads but requires derivation for EGL.

- For profiles: Go to Report > Graph > Profile. Select a node chain (e.g., reservoir to tank). Plot "Hydraulic Head" vs. distance. This approximates HGL (head includes elevation effects).

- To derive EGL: Export node heads and pipe velocities via Report > Table (include elevation, head, velocity). Compute HGL = V22g externally (velocity head often negligible, <1 ft at 5 ft/s).

- Map view: Display heads or pressures with color legends; animate over time.

- Export results to Excel for custom plots: Plot distance vs. HGL (elevation + pressure head) and EGL.

Comparison of Tools for EGL vs HGL in Water Distribution Systems

| Tool | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| EPANET | Free, simple steady-state simulations, profile plots for HGL | No direct EGL plot, limited transients |

| WaterGEMS | Transient analysis, built-in surge modeling, GIS integration | Paid, steeper learning curve |

| InfoWater | ArcGIS compatibility, optimization tools | Enterprise-focused, costly |

Subjectively, seeing a well-calibrated model align with field data brings that spark of confidence every engineer craves.

6. Interpreting HGL and EGL Profiles

Once you've calculated or modeled your HGL and EGL, the key step is analyzing what these lines reveal about your system's performance. Visualize them on a graph, with pipe distance on the x-axis and head (in feet) on the y-axis. The HGL, typically a solid blue line, tracks pressure potential; the EGL, dashed red and positioned above, includes kinetic energy. These profiles serve as diagnostic tools, highlighting efficiencies, risks, and areas for improvement.

Begin with fundamentals. A gradual HGL drop shows typical friction losses from pipe walls and fittings. A sudden steepening warrants review: it may point to undersized pipes, obstructions, or high demands inducing turbulence. A nearly flat HGL could indicate stagnant flow, promoting sediment or bacterial issues. Critically, if the HGL falls below the pipe elevation, it signals negative pressure, risking cavitation where vapor bubbles form and collapse, eroding pumps and pipes and leading to failures.

The EGL provides further details, parallel to the HGL in constant-velocity areas but separating where speed varies. Expect an EGL rise at pumps matching the imparted head, validating operation. If the EGL-HGL gap expands downstream, it suggests rising velocity head, signaling fast flows in constricted sections that invite erosion-corrosion. That gap acts as an alert for inefficiency, prompting pipe resizing or controls to limit velocities under 8 ft/s.

Gain more by adding context. In gravity systems, an uneven HGL decline might cause tank overflows or air entrapment. In pressurized ones, track EGL reductions at valves, where cumulative minor losses increase costs. A useful technique is superimposing demand patterns to observe peak-hour shifts, uncovering issues like inadequate pressures.

Systematize with this checklist:

- Identify negative HGL areas: Address to prevent cavitation.

- Assess slope gradients: Align with standards (e.g., <5 ft/1000 ft for efficient mains).

- Evaluate EGL-HGL gaps: If >2 ft, review diameters for velocity management.

- Examine jumps/drops: Ensure pumps deliver expected head; fittings minimize losses.

- Test extremes: Profile under peak/low demands to predict problems.

Key Features in HGL and EGL Profiles for Water Distribution Analysis

| Profile Feature | Interpretation | Potential Action |

|---|---|---|

| Steep HGL drop | High friction losses | Upsize pipes or clean internals |

| HGL below pipe | Negative pressure | Install air release valves or surge tanks |

| EGL upward jump | Pump addition | Confirm efficiency with curve data |

| Widening EGL-HGL gap | Increasing velocity | Reduce flow or enlarge sections |

| Irregular wiggles | Transient effects (e.g., hammer) | Add surge protection devices |

There's a distinct satisfaction in interpreting these profiles, converting curves into practical measures that ensure reliable water flow. This bridges theory and infrastructure reality.

7. Critical Design Implications

HGL and EGL aren't abstract concepts; they drive real-world decisions in water system design, ensuring safety, efficiency, and compliance. Their profiles inform everything from pipe sizing to surge protection, with distinct applications across system types. Understanding these implications helps engineers avoid common pitfalls like under-pressurization or hydraulic transients that compromise service.

7.1 Pressurized systems

In fully pressurized networks, where pumps maintain flow against elevation and friction, the HGL must stay above a minimum threshold, typically 20 psi at service connections, to prevent complaints about weak showers or irrigation failures. If the HGL sags too low, it risks drawing air into pipes or contaminating water through backflow. Design here focuses on balancing pressures: use EGL to optimize pump curves, ensuring energy additions counteract losses without over-pressurizing and bursting mains. A practical tip is to simulate fire-flow demands; if HGL drops below 20 psi, add pressure-reducing valves or booster stations. Getting this right is rewarding, as it directly impacts daily user experience.

7.2 Gravity-flow and partial gravity systems

Gravity systems rely on elevation differences for flow, so the HGL should decline naturally from reservoirs downhill, without artificial boosts. This prevents overflows at tanks or low spots where water stagnates, fostering quality issues. Partial gravity setups, blending downhill flow with occasional pumps, demand careful HGL monitoring to avoid vacuums in high-elevation segments. Critical here is topographic alignment: if HGL intersects ground level, install vents to release trapped air. Experience says: integrate climate data for seasonal variations; warmer water reduces density, subtly altering HGL slopes and risking summertime overflows.

7.3 Pumped systems and surge anticipation

Pumped networks see EGL spikes at stations, reflecting added mechanical energy, but this introduces surge risks like water hammer from sudden stops. Model transients using EGL to predict pressure waves that could exceed pipe ratings, causing leaks or ruptures. Anticipate by incorporating surge tanks or variable-speed drives, keeping EGL fluctuations within 10-20% of steady-state. In high-rise or long-distance lines, EGL guides check-valve placement to dampen reverses.

Design Implications of HGL and EGL in Various Systems

| System | Key HGL Focus | Key EGL Focus | Design Tip |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pressurized | Minimum pressure thresholds | Pump efficiency and losses | Simulate peak demands |

| Gravity | Natural decline, no vacuums | Minimal, unless partial pumps | Align with topography |

| Pumped | Surge-prone transitions | Energy additions and transients | Add protective devices |

8. Common Errors and Catastrophic Consequences

Errors in HGL and EGL analysis aren't mere oversights; they can cascade into system-wide failures, financial losses, and safety hazards. By examining frequent mistakes, designers can learn to sidestep them.

A primary error is neglecting minor losses from fittings, valves, or bends, which leads to underestimated head drops. In calculations, these might seem insignificant (e.g., K-factors of 0.5-1.0), but in long networks, they accumulate, skewing HGL profiles and causing unexpected low pressures. Another common issue is assuming constant demands; ignoring diurnal patterns results in overly optimistic EGL during peaks, overlooking surges that hammer pipes. Mis-calibrating roughness coefficients (e.g., using C=140 for aged cast iron instead of 100) inflates efficiency predictions, leading to undersized components. Finally, failing to account for elevation data inaccuracies, off by even 5 ft, distorts the entire profile, risking vacuums or overflows.

The consequences can be dire. Underestimated losses might trigger cavitation, where collapsing vapor bubbles pit metal surfaces, shortening pump life from years to months and costing thousands in replacements. In extreme cases, negative HGL causes pipe collapses under vacuum, as seen in urban mains where undetected errors led to street-flooding bursts. Surges from poor EGL anticipation can exceed pressure ratings, fracturing joints and contaminating supplies with soil ingress, prompting boil-water advisories and public health alerts. Energy waste is subtler but cumulative: oversized pumps from flawed modeling spike utility bills, eroding budgets over time.

In a Southeast Asian diversion system project, an overlooked downstream boundary condition created a modeled HGL that ignored backwater effects, resulting in a real-world hydraulic jump that collapsed the intake structure shortly after commissioning. The Kang-Wei-Kou (KWK) Diversion in Taiwan failed on August 10, 2014, due to scouring from low downstream levels, as analyzed in Liang et al. [7]. It underscored the peril of incomplete EGL dissipation analysis, delaying operations by weeks and inflating costs.

Conversely, proactive modeling shines: In Midwestern U.S. municipal upgrades, accurate EGL simulations identified inefficient segments, allowing booster additions that slashed energy use and garnered regulator approval without publicity [8].

Always cross-verify with field data.

Common HGL/EGL Errors and Mitigation in Water Systems

| Error Type | Cause | Consequence | Prevention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ignoring minor losses | Overlooking K-factors | Low pressures, inefficiencies | Include in head loss equations |

| Constant demand assumption | Neglecting patterns | Surge events, hammer | Use extended-period simulations |

| Wrong roughness | Material misestimation | Undersized pipes | Calibrate with actual data |

| Elevation errors | Survey inaccuracies | Vacuums/overflows | GPS/GIS verification |

10. Practical Rules of Thumb and Checklist

Drawing from decades of field experience, these rules of thumb provide quick, reliable guidelines for HGL and EGL work. They supplement formal calculations, helping you spot issues fast during design or troubleshooting. Use them as starting points, adjusted against site-specific data.

- Limit HGL drop to 5-10 ft per 1000 ft in mains to minimize energy losses and maintain pressures.

- Keep velocities under 5 ft/s in distribution lines; above 8 ft/s risks erosion and noise.

- Add 10-20% safety margin to pump head to cover unmodeled losses and aging.

- Ensure HGL exceeds ground elevation by at least 2 ft to avoid negative pressures.

- For tanks, set float levels so HGL stays 5-10 ft below overflow during peaks.

- In hilly terrain, place air valves where HGL peaks to release trapped gases.

- Use C=100-120 for aged pipes in Hazen-Williams; test with flow data if possible.

- Check EGL rise at pumps equals rated head minus 5% for efficiency losses.

- Model at least three scenarios: average, peak, and fire flow demands.

- Calibrate models to within 5% of field pressures before finalizing designs.

Checklist for HGL/EGL Verification

- Confirm all elevations from surveys or GIS

- Include minor losses for every fitting

- Run steady-state and extended-period simulations

- Plot VPL and ensure HGL clearance

- Compare velocities against 5-8 ft/s limits

- Validate pump curves with manufacturer data

- Test for negative pressures under low demand

- Review slopes for excessive drops (>10 ft/1000 ft)

- Export results to spreadsheets for cross-checks

- Document assumptions for future audits

11. Case Study 1: Water Distribution Network Analysis in Chirala Municipality

Background and Context

This case study is based on a 2016 peer-reviewed paper by G. Anisha and colleagues, titled "Analysis and Design of Water Distribution Network Using EPANET for Chirala Municipality in Prakasam District of Andhra Pradesh," published in the International Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences. The research evaluates the existing intermittent dead-end water distribution system in Chirala, India, covering an area of 13.30 km² with a 2011 population of 87,200, projected to reach 134,398 by 2041. The installed capacity is 10 million liters per day (MLD), but current demand is 15.44 MLD, rising to 19.08 MLD by 2041, necessitating hydraulic analysis for redesign [10].

Problems Addressed

The system suffers from inadequate pressures in peripheral zones, uneven flow distribution due to dead-end layouts, high head losses in small-diameter pipes, and insufficient capacity for future growth. These lead to unreliable supply, potential leaks, and inefficiencies, highlighting the need for evaluation to ensure minimum pressures and velocities while recommending upgrades.

Methods and Tools

EPANET was employed for extended-period simulation over 24 hours, solving nonlinear equations for flows, pressures, and head losses. The network was digitized in AutoCAD and imported via EPACAD, with demands allocated using the unit area method (1.438 L/m²/day). Pipe roughness was set at C=145 for plastic pipes. The hydraulic grade line (HGL) was calculated as HGL = elevation + pressure head at nodes. Head losses used the Hazen-Williams formula, with the system zoned into five areas for targeted analysis.

Specific Assessments

- Pressures and HGL: Nodal pressures ranged from 13.86 m to 16.74 m, with HGL derived from elevations (4.5-5.5 m above mean sea level) plus pressure head.

- Velocities: Flows varied from 0.01 m/s to 1.08 m/s, assessed against limits of 0.6-2.5 m/s.

- Head Losses: Unit losses ranged from 0.01 m/km to 10.46 m/km, higher in 100 mm pipes and dead-end branches.

Results and Outcomes

Pressures met minimum standards (above 7-10 m desired) but were marginal in distant nodes, indicating uneven distribution. Velocities were acceptable, avoiding scour or deposition. Elevated losses in certain links pointed to diameter constraints. The study concluded the dead-end system is unsuitable for future demands and recommended a grid/ring redesign, larger pipes, and two new 2 MLD reservoirs to achieve equitable pressures and flows.

Application to HGL and EGL Concepts

This case study applies HGL in evaluating network performance, where profiles reveal pressure deficiencies and head losses, informing redesigns for balanced distribution. Energy balances are implied through head loss computations, aligning with EGL principles for efficiency. The analysis, verifiable via the original paper on platforms like ResearchGate and Neliti, demonstrates how HGL guides urban system upgrades, reinforcing modeling (Section 5) and design implications (Section 7).

12. Case Study 2: Hydraulic Analysis of a Municipal Water Network with Pumps and Demands

Background and Context

This case study is drawn from a 2002-2025 course notes document by Donald V. Chase, titled "Fundamentals of Hydraulics: Closed Conduits," hosted in the University of Dayton's eCommons repository. The chapter presents an example of a municipal water distribution network supplying varied demands, including a hospital, golf course, and schools, to illustrate energy and pressure concepts in urban systems [1].

Problems Addressed

The example tackles maintaining positive pressures and flows in networks with elevation variations and high demands, focusing on calculating distributions, head losses, and profiles to prevent issues like negative pressures or inefficiencies from undersized components.

Methods and Tools

Manual hydraulic calculations, compatible with EPANET, solve for flows using continuity at nodes and head losses via the Hazen-Williams formula with C-factors (90–120). Minor losses incorporate K-factors. Pump heads are based on curves (e.g., Pump #1 adds 168.563 ft at 2130 gpm). The hydraulic grade line (HGL) is computed as HGL = elevation + pressure head, starting from the reservoir at 1550 ft. The energy grade line (EGL) is defined as EGL = HGL + velocity head, though velocity head is neglected as minor (e.g., 1 ft at 8 ft/s). Pressures derive from HGL minus elevation.

Specific Assessments

- System Components: Reservoir at 1550 ft, junctions with elevations (1320-1580 ft) and demands (e.g., hospital: 500 gpm), pipes with lengths (250-4000 ft) and diameters (6-24 in), and two pumps.

- Flows and Head Losses: Pipe flows from 75-2130 gpm; total losses from 1.003 ft (Pipe P2) to 253.486 ft (Pipe P9), including friction and minors.

- HGL Profile: Plotted from reservoir to Node J, with pump jumps (e.g., +168.563 ft) and loss declines.

- Pressures: From HGL (e.g., Node A: 168.939 psi; hospital: 126.894 psi), meeting minimums.

Results and Outcomes

The network sustains positive pressures (97-168 psi), with HGL dropping from 1717 ft at pump discharge to 1624 ft at Node J. High losses in Pipe P9 signal bottlenecks. The example confirms hydraulic viability, showing how profiles guide pump placement and sizing for reliable supply.

Application to HGL and EGL Concepts

This case study defines and applies both HGL and EGL in a pumped network, with HGL profiles showing energy dynamics and EGL highlighting velocity head's role (though often negligible). The document from eCommons confirms these elements, providing a technical basis for interpretation (Section 6) and pumped systems (Section 7.3), where EGL verifies energy additions and losses.

13. Conclusion

This article provides for you a comprehensive examination of the hydraulic grade line (HGL) and energy grade line (EGL) as fundamental tools for water distribution system analysis and design. HGL, defined as the sum of pressure head and elevation

and EGL, the total mechanical energy per unit weight

embody Bernoulli's principles, enabling quantification of pressure distributions, loss mechanisms, and flow dynamics in gravity-fed and pressurized networks.

You are also taught skills in manual calculations via derivations of head loss equations such as Darcy-Weisbach and Hazen-Williams, incorporating friction, minor losses, and velocity. Modeling with EPANET scales this to network simulations, facilitating steady-state and transient profile generation. Profile interpretation reveals key patterns: HGL slopes indicate dissipation, EGL divergences highlight kinetic inefficiencies, with checklists for diagnosing negatives or surges.

Design implications emphasize HGL for maintaining minima (e.g., 20 psi) against vacuums and EGL for pump optimization to prevent cavitation. Errors like omitted losses or roughness miscalibrations, leading to bursts or waste, are mitigated by the vapor pressure line (VPL) as a cavitation safeguard. Rules and case studies demonstrate applications in urban and pumped systems.

Mastery of HGL and EGL advances system precision, reducing costs and enhancing resilience. These concepts open avenues to explore transient EGL dynamics or VPL integration with advanced modeling, translating fluid mechanics into robust infrastructure solutions.

14. Glossary

AHP (Analytical Hierarchy Process): A structured technique for organizing and analyzing complex decisions, based on mathematics and psychology, used in risk assessments to weigh factors like structural and customer risks in water systems.

AWWA (American Water Works Association): A professional organization that sets standards for water utilities, including velocity limits (e.g., 5-8 ft/s) to prevent erosion in pipes.

C-factor: The roughness coefficient in the Hazen-Williams equation, representing pipe interior condition; values range from 100 (aged pipes) to 145 (smooth plastic).

Cavitation: The formation of vapor bubbles in low-pressure zones, followed by their implosive collapse, which erodes surfaces like pump impellers and pipe walls.

cfs (Cubic Feet per Second): A unit of volumetric flow rate commonly used in US customary systems for water distribution calculations.

Darcy-Weisbach Equation: A formula for calculating frictional head loss in pipes: hL = f(LD) V22g where f is the friction factor, L length, D diameter, V velocity, and g gravity.

du/dy: The velocity gradient in fluid flow, used in shear stress calculations for deriving head loss in laminar regimes.

EGL (Energy Grade Line): The line representing total mechanical energy per unit weight along a flow path: EGL = pγ + z + V22g sloping downward due to irreversible losses.

EPANET: Open-source software developed by the U.S. EPA for modeling water distribution systems, solving hydraulics using the gradient method for flows, pressures, and grade lines.

Friction Factor: A dimensionless value in the Darcy-Weisbach equation, determined empirically for turbulent flow or exactly for laminar

GIS (Geographic Information System): Software for capturing, storing, and analyzing spatial data, integrated with tools like InfoWater for network mapping and elevation verification.

g (Acceleration Due to Gravity): A constant (32.2 ft/s² in US units) used in velocity head (V²/2g) and other energy calculations.

GPM (Gallons per Minute): A unit of flow rate in US customary systems, often used in pump curves and demand assignments.

Hazen-Williams Equation: An empirical formula for head loss in water pipes: in US units, hL: Head loss (ft), L: Length of pipe (ft), Q: Flow rate (cfs), C: Roughness coefficient, D: Pipe diameter (ft).

h_f (Frictional Head Loss): The energy loss per unit weight due to pipe wall friction, calculated in formulas like Hazen-Williams. hL (Head Loss): The reduction in total head due to friction, fittings, or other resistances, subtracted in the modified Bernoulli equation.

Head Loss: The reduction in total head due to friction, fittings, or other resistances, subtracted in the modified Bernoulli equation.

HGL (Hydraulic Grade Line): The locus of points summing pressure head and elevation: HGL = pγ + z indicating the height water rises in a piezometer.

K-factor: The coefficient for minor losses in fittings or valves, used to compute additional head loss as hm = Kv22g.

L (Pipe Length): The distance along a conduit, a key parameter in head loss equations.

MLD (Million Liters per Day): A metric unit for daily water demand or capacity in distribution systems.

μ (Dynamic Viscosity): A fluid property measuring resistance to shear, used in laminar flow derivations like Hagen-Poiseuille for head loss.

(Pressure Head): The energy per unit weight due to pressure, where p is pressure and γ specific weight.

Patm (Atmospheric Pressure): The ambient pressure (14.7 psi at sea level), subtracted in VPL calculations to find relative vapor head.

Pv (Vapor Pressure): The pressure at which a liquid boils, used in VPL as to determine cavitation thresholds (e.g., -33 ft for water at 68°F).

Q (Flow Rate): The volume of fluid passing per unit time, expressed in cfs, GPM, or LPS in hydraulic equations.

R (Hydraulic Radius): The cross-sectional area divided by wetted perimeter, used in open-channel or pipe flow resistance formulas.

Re (Reynolds Number): A dimensionless ratio distinguishing laminar from turbulent flow, critical for friction factor selection. Where, ρ: fluid density, V: flow velocity, D: pipe diameter, μ: dynamic viscosity.

S (Hydraulic Slope): The energy gradient or head loss per unit length, used in Hazen-Williams as a flow driver.

τ (Shear Stress): The force per unit area at the pipe wall, given by in laminar flow derivations.

(Velocity Head): The kinetic energy per unit weight, the difference between EGL and HGL.

VPL (Vapor Pressure Line): A reference line at vapor pressure head (e.g., -33 ft), plotted below HGL to predict cavitation risks.

WAWQI (Weighted Arithmetic Water Quality Index): A method aggregating parameters like pH and turbidity into a single score for assessing customer-side risks.

Water Hammer: A pressure surge from sudden flow changes (e.g., valve closure), modeled via transients to prevent pipe damage.

z (Elevation Head): The potential energy per unit weight due to height above a datum, a component of both HGL and EGL.

15. Frequently Asked Questions

Q: How does the choice between Darcy-Weisbach and Hazen-Williams equations affect HGL calculations in aging urban networks? A: Darcy-Weisbach provides more accuracy for turbulent flows and variable roughness, ideal for aged pipes where friction factors evolve; it yields precise HGL drops but requires iteration. Hazen-Williams simplifies with empirical C-factors (e.g., 100 for corroded iron), suiting quick estimates, but overestimates in non-water fluids or extreme velocities. In real networks, adjust both against field data to avoid underestimated losses, as seen in case studies like Chirala's high-loss small pipes.

Q: In EPANET, why might the simulated HGL not match field measurements, and how can I adjust for real-world discrepancies? A: Discrepancies often arise from unmodeled minor losses, inaccurate demands, or outdated roughness (e.g., C=120 vs. actual 100 in aged systems). Adjust by calibrating with gauge data to aim for ±5% pressure match and incorporate time-varying patterns or GIS elevations. For twists like seasonal biofilm buildup, reduce C by ~15% in simulations to refine HGL profiles.

Q: What happens to the EGL in a pumped system during a power outage, and how does VPL help mitigate risks? A: EGL drops rapidly as pump head vanishes, potentially causing reverse flow or surges. If the HGL falls below VPL (e.g., -33 ft at 68°F), cavitation follows, eroding components. Use VPL in transient modeling (e.g., via WaterGEMS) with a 5-10 ft margin; install surge tanks to maintain EGL stability, preventing failures like those in high-rise boosters.

Q: Can HGL interpretation predict water quality issues in gravity-fed networks, and if so, how? A: Yes, flat HGL segments signal stagnation, fostering bacterial growth or sediment; steep drops indicate high velocities risking resuspension. Monitor for HGL <5 ft/1000 ft slopes to avoid quality degradation. In practice, overlay demand patterns: if HGL nears ground during lows, add loops to promote circulation, as implied in urban redesigns.

Q: How do climate variations impact EGL slopes in long-distance transmission lines? A: Warmer temperatures raise vapor pressure, elevating VPL and tightening cavitation margins, while viscosity changes alter friction (e.g., 10% head loss increase at 50°F vs. 100°F). Model seasonally adjusted roughness; in cold climates, frozen ground shifts elevations, steepening EGL. Use experienced insights: factor 5% buffer in EGL for thermal expansions to ensure year-round reliability.

Q: In a mixed gravity-pressurized system, how does ignoring minor losses affect HGL accuracy at fittings? A: It underestimates drops in bends/valves (K=0.5-1.0), leading to optimistic HGL and real-world low pressures. Calculate explicitly as hm = Kv22g in EPANET, add coefficients to adjust for minor losses. Real twist: in high-velocity zones (>5 ft/s), minors amplify erosion, as seen in pumped networks. Correct to field tests for tighter profiles.

Q: What role does EGL play in optimizing booster pump placement for elevated terrains? A: EGL jumps at boosters restore energy lost to elevation; place them where EGL nears minimum to minimize stations while keeping HGL above 20 psi. Simulate in EPANET to identify optimal locations for energy efficiency, potentially achieving 20% or more in electricity cost reductions through targeted scheduling and additions. Consider transients to avoid hammer, ensuring EGL fluctuations stay within 10-20%.

Q: How can VPL integration prevent failures in high-altitude water systems? A: At elevation, lower atmospheric pressure drops VPL (e.g., -28 ft at 5,000 ft), increasing cavitation risk. Plot VPL adjusted for altitude and temperature; maintain HGL 10 ft above to buffer surges. In practice, like Andean or Rocky Mountain networks, this averts impeller pitting. Use tools like WaterHAMMER for dynamic checks.

16. Bibliography

Have a project you would like to discuss?

Contact Ecologix Environmental Systems today to learn more about our engineered solutions.

Contact Us